A couple of years ago I implemented a mail submission component capable of interacting with SMTP servers over the internet for delivering e-mail messages. Developing it helped me better understand the inner workings of e-mail transmission, which I share in this article.

I named this component “Mail Broker” as not to be confused with “Message Submission Agent” already defined in RFC 6409 along with other participating agents of electronic mail infrastructure:

Message User Agent (MUA): A process that acts (often on behalf of a user and with a user interface) to compose and submit new messages, and to process delivered messages.

Message Submission Agent (MSA): A process that conforms to this specification. An MSA acts as a submission server to accept messages from MUAs, and it either delivers them or acts as an SMTP client to relay them to an MTA.

Message Transfer Agent (MTA): A process that conforms to SMTP-MTA. An MTA acts as an SMTP server to accept messages from an MSA or another MTA, and it either delivers them or acts as an SMTP client to relay them to another MTA.

This Mail Broker is intended for sending e-mail messages directly from within .NET applications supporting alternate views and file attachments. Let’s take a look at some sample usage code (C#) to clear it out:

using (var msg = new MailMessage())

{

msg.From = new MailAddress("admin@mydomain.com", "System Administrator");

msg.To.Add(new MailAddress("john@yahoo.com"));

msg.CC.Add(new MailAddress("bob@outlook.com"));

msg.Subject = "Hello World!";

msg.Body = "<div>Hello,</div><br><br>" +

"<div>This is a test e-mail with a file attached.</div><br><br>" +

"<div>Regards,</div><br><div>System Administrator</div>";

msg.IsBodyHtml = true;

var plain = "Hello,\n\nThis is a test e-mail with a file attached.\n\n" +

"Regards,\nSystem Administrator";

var alt = AlternateView.CreateAlternateViewFromString(plain, new ContentType("text/plain"));

msg.AlternateViews.Add(alt);

var filePath = @"...\some-folder\pretty-image.png";

var att = new Attachment(filePath);

msg.Attachments.Add(att);

var config = new BrokerConfig { HostName = "mydomain.com" };

using (var broker = new MailBroker(config))

{

var result = broker.Send(msg);

Console.WriteLine($"Delivered Messages: {result.Count(r => r.Delivered)}");

}

}

The key difference about it is that messages can be sent from any source e-mail address directly to destination SMTP servers, as long as you perform required sender domain and IP address authentication steps to prevent being blacklisted for misuse (more on that below).

I’ve put it together integrating a couple of GitHub projects, fixing bugs, and implementing my own code as well. You can access its repository on GitHub here.

A lot of networking, encoding and security concepts were involved in this experiment, which I share in the following sections. I believe they are valuable for anyone trying to get a picture of what happens under the hood when we send an ordinary e-mail.

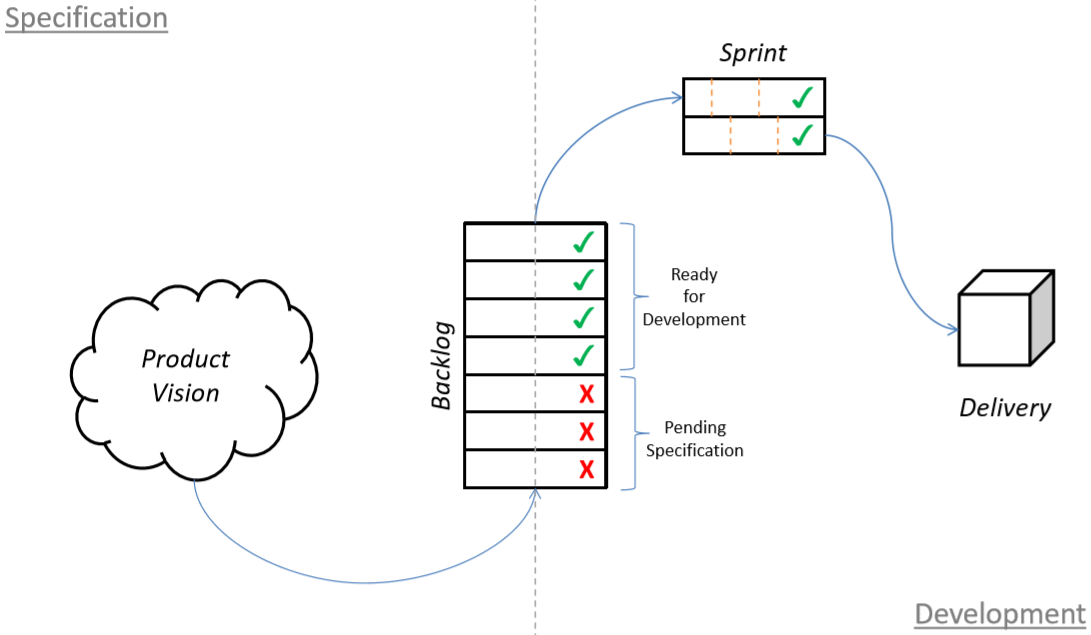

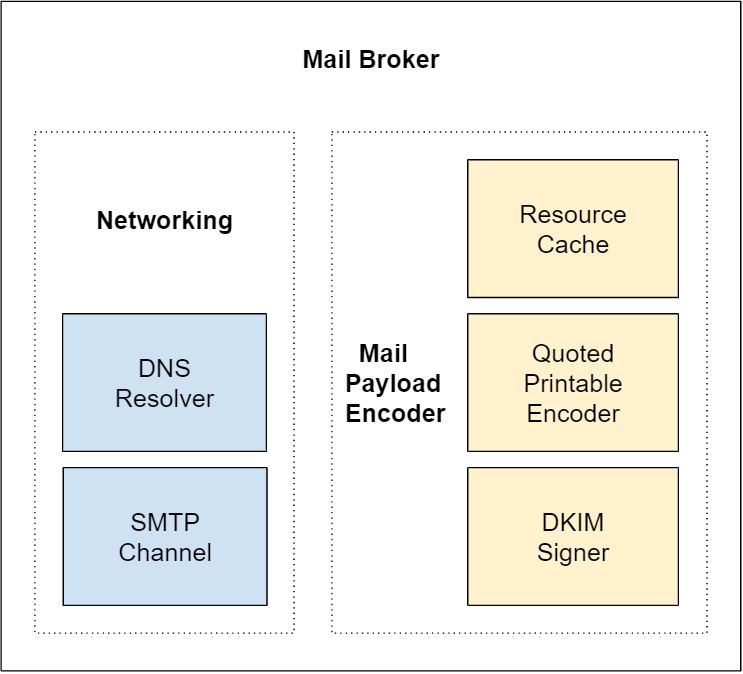

Internal Structure

The diagram below illustrates the Mail Broker internal structure:

It is implemented on top of networking and message encoding components. Native framework components / resources such as TcpClient, RSACryptoServiceProvider, SHA256CryptoServiceProvider, Convert.ToBase64String and others were omitted from the diagram for simplicity.

I also took advantage of .NET MailMessage class that can be sent using the now obsolete System.Net.Mail.SmtpClient as it already represents all fields and views of a typical e-mail message.

Sending a Message

Internally the message delivery is performed by the following piece of code:

var mxDomain = ResolveMX(group);

if (!string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(mxDomain))

{

Begin(mxDomain);

Helo();

if (StartTls())

Helo();

foreach (var addr in group)

results.Add(Send(message, addr));

Quit();

}

else

{

foreach (var addr in group)

results.Add(new Result(delivered: false, recipient: addr));

}

This piece is executed for each destination email address (To, Cc, Bcc). First it resolves mail exchanger records (MX record) for destination addresses grouped by domain, as to find out where to connect for submitting the message. If a MX domain is not found the code marks delivery for this recipient as failed. However, if the MX domain is found it proceeds by beginning an SMTP session with this external mail server.

The Mail Broker will connect to the SMTP server on port 25, receive a “ServiceReady” status code, and start the conversation by sending a HELO command. Then it tries to upgrade this plain text connection to an encrypted connection by issuing a STARTTLS command. If that’s not supported by the mail server it falls back to the plain text connection for delivering the message, which is really bad security wise, but is the only option for delivering the message in this case 😕

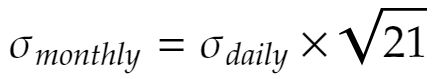

We all know that communication on the internet should always be encrypted, but I was amazed to find out how many SMTP servers still don’t support it and communicate in plain text, just hoping that no one is watching! Google’s Transparency Report indicates that today more than 10% of all e-mail messages sent by Gmail are still unencrypted, usually because the receiving end doesn’t support TLS.

Moving forward, after upgrading the connection, the code will issue SMTP commands for individually sending the message to each destination address in this domain group, and after that QUIT the session. The sequence for sending the message is contained in the method showed below:

private Result Send(MailMessage message, MailAddress addr)

{

WriteLine("MAIL FROM: " + "<" + message.From.Address + ">");

Read(SmtpStatusCode.Ok);

WriteLine("RCPT TO: " + "<" + addr.Address + ">");

SmtpResponse response = Read();

if (response.Status == SmtpStatusCode.Ok)

{

WriteLine("DATA ");

Read(SmtpStatusCode.StartMailInput);

WritePayload(message);

WriteLine(".");

response = Read();

}

else

{

WriteLine("RSET");

Read(SmtpStatusCode.ServiceReady, SmtpStatusCode.Ok);

}

return new Result(

delivered: response.Status == SmtpStatusCode.Ok,

recipient: addr,

channel: channel,

response: response

);

}

This code reproduces the typical SMTP transaction scenario described in RFC5321:

1. C: MAIL FROM:<Smith@bar.com>

2. S: 250 OK

3. C: RCPT TO:<Jones@foo.com>

4. S: 250 OK

5. C: DATA

6. S: 354 Start mail input; end with <CRLF>.<CRLF>

7. C: Blah blah blah...

8. C: ...etc. etc. etc.

9. C: .

10. S: 250 OK

11. C: QUIT

12. S: 221 foo.com Service closing transmission channel

Lines 7 through 9 perform the transmission of the encoded mail message payload. This is handled by the WritePayload(message) and subsequent WriteLine(".") method calls in the code snippet above, which we will get into more detail in the next section.

Encoding the Message

Preparing the message for transmission is tiresome, with lots of minor details to consider. It can be broken down into two parts, the header and the content. Let’s start with the header, the code below was extracted from the MailPayload class, and is responsible for generating the encoded message headers for transmission:

WriteHeader(new MailHeader(HeaderName.From, GetMessage().From));

if (GetMessage().To.Count > 0)

WriteHeader(new MailHeader(HeaderName.To, GetMessage().To));

if (GetMessage().CC.Count > 0)

WriteHeader(new MailHeader(HeaderName.Cc, GetMessage().CC));

WriteHeader(new MailHeader(HeaderName.Subject, GetMessage().Subject));

WriteHeader(new MailHeader(HeaderName.MimeVersion, "1.0"));

if (IsMultipart())

{

WriteHeader(HeaderName.ContentType, "multipart/mixed; boundary=\"" + GetMainBoundary() + "\"");

WriteLine();

WriteMainBoundary();

}

These are pretty much straight forward:

- From: Specifies the author(s) of the message

- To: Contains the address(es) of the primary recipient(s) of the message

- Cc: Contains the addresses of others who are to receive the message, though the content of the message may not be directed at them

- Subject: Contains a short string identifying the topic of the message

- MimeVersion: An indicator that this message is formatted according to the MIME standard, and an indication of which version of MIME is used

- ContentType: Format of content (character set, etc.)

If the message is multipart, i.e., contains any alternate view or attachment, then there’s a need to define a content boundary for transmitting all content parts, which can have different content types and encodings.

Notice that I’m not using the Bcc header, as RFC 822 leaves it open to the system implementer:

Some systems may choose to include the text of the “Bcc” field only in the author(s)’s copy, while others may also include it in the text sent to all those indicated in the “Bcc” list

There are dozens of other headers available providing more elaborate functionality. The initial IANA registration for permanent mail and MIME message header fields can be found in RFC4021, and is overwhelming. You can see I only covered the most basic headers in this experiment.

Now let’s look at how the message content is being handled:

private void WriteBody()

{

var contentType = (GetMessage().IsBodyHtml ? "text/html" : "text/plain");

WriteHeader(HeaderName.ContentType, contentType + "; charset=utf-8");

WriteHeader(HeaderName.ContentTransferEncoding, "quoted-printable");

WriteLine();

WriteLine(QuotedPrintable.Encode(GetMessage().Body));

WriteLine();

}

The body content can be sent as plain text or as HTML, and an additional ContentType header will indicate which one is used. There’s also a ContentTransferEncoding header present, which in this case is always adopting Quoted-printable, a binary-to-text encoding system using printable ASCII characters to transmit 8-bit data over a 7-bit data path. It also limits line length to 76 characters for legacy reasons (RFC2822 line length limits):

There are two limits that this standard places on the number of characters in a line. Each line of characters MUST be no more than 998 characters, and SHOULD be no more than 78 characters, excluding the CRLF

Attachments binary data are encoded to Base64, yet another a binary-to-text encoding system, before being written to the underlying SMTP channel:

private void WriteAttachment(Attachment attachment)

{

WriteHeader(HeaderName.ContentType, attachment.ContentType.ToString());

WriteHeader(HeaderName.ContentDisposition, GetContentDisposition(attachment));

if (!string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(attachment.ContentId))

WriteHeader(HeaderName.ContentID, "<" + attachment.ContentId + ">");

WriteHeader(HeaderName.ContentTransferEncoding, "base64");

WriteLine();

WriteBase64(attachment.ContentStream);

WriteLine();

}

Even though Base64 encoding adds about 37% to the original file length it is still widely adopted today. It may seem strange and wasteful, but, for historical reasons, it became the standard for transmitting email attachments and it would require huge efforts to change this.

The code for writing headers and content related to alternative views was omitted for simplicity. If you’re curious you can find it in the MailPayload class source code on GitHub.

Securing the Message

Suppose the message was encoded and transmitted as described above, how can we trust the destination mail server not to tamper with the message’s headers and contents? The answer is we can’t! There’s nothing preventing it from changing the message before delivering it to the end user so far.

Fortunately, to address this issue we can employ the DomainKeys Identified Mail (DKIM) authentication method:

DKIM allows the receiver to check that an email claimed to have come from a specific domain was indeed authorized by the owner of that domain. It achieves this by affixing a digital signature, linked to a domain name, to each outgoing email message. The recipient system can verify this by looking up the sender’s public key published in the DNS. A valid signature also guarantees that some parts of the email (possibly including attachments) have not been modified since the signature was affixed.

I’ve integrated a DKIM Signer component to the Mail Broker for signing encoded messages before sending them. To use it we need to provide a DkimConfig object to the Mail Broker constructor:

public class DkimConfig

{

public string Domain { get; set; }

public string Selector { get; set; }

public RSAParameters PrivateKey { get; set; }

}

The domain and selector parameters are used by receiving SMTP servers for verifying the DKIM signature header, which perform a DNS lookup on <selector>._domainkey.<domain> for retrieving a TXT record containing the signature public key information, for instance:

"v=DKIM1; k=rsa; t=s; p=MIGfMA0GCSqGSIb3DQEBAQUAA4GNADCBiQKBgQDDmzRmJRQxLEuyYiyMg4suA2Sy

MwR5MGHpP9diNT1hRiwUd/mZp1ro7kIDTKS8ttkI6z6eTRW9e9dDOxzSxNuXmume60Cjbu08gOyhPG3

GfWdg7QkdN6kR4V75MFlw624VY35DaXBvnlTJTgRg/EW72O1DiYVThkyCgpSYS8nmEQIDAQAB"

This configuration object is passed to the MailPayload class for writing signed content:

private void WriteContent()

{

if (config != null)

WriteSignedContent();

else

WriteUnsignedContent();

}

private void WriteSignedContent()

{

var content = new MailPayload(GetMessage());

var dkim = new DkimSigner(config);

var header = dkim.CreateHeader(content.Headers, content.Body, signatureDate);

WriteHeader(header);

Write(content);

}

As you can see the WriteSignedContent instantiates another MailPayload class without passing the DkimConfig constructor parameter. This results in encoding the mail message using the WriteUnsignedContent method. Once headers and body are encoded it instantiates a DkimSigner class and creates a signature header that precedes the content in the mail data transmission.

Making this DKIM signing component work was the most difficult task in this project. You can take a closer look at how it works from MailPayload unit tests here.

Authenticating Senders

At the beginning of this post I wrote that the Mail Broker can send messages from any source e-mail address, just like Mailchimp can send messages on your behalf without you ever giving it your e-mail password. How’s that possible? you may ask, and the answer is because e-mail delivery is a reputation based system.

But keep this in mind, sending the message doesn’t mean it will be accepted, specially if the sender doesn’t have a good reputation. Here’s what happens when I try to send a message from no-reply@thomasvilhena.com to a Gmail mailbox from a rogue server (IP obfuscated):

421-4.7.0 [XX.XXX.XXX.XXX XX] Our system has detected that this message is

421-4.7.0 suspicious due to the very low reputation of the sending IP address.

421-4.7.0 To protect our users from Spam, mail sent from your IP address has

421-4.7.0 been temporarily rate limited. Please visit

421 4.7.0 https://support.google.com/mail/answer/188131 for more information. e6si8481552qkg.297 - gsmtp

You see, Gmail found the message suspicious, and as I checked it didn’t even reach the destination mailbox spam folder, the sender reputation was so low the message wasn’t even spam worthy!

Here’s what Gmail suggests to prevent messages from being marked as Spam, or not being delivered to the end user at all:

- Verify the sending server PTR record. The sending IP address must match the IP address of the hostname specified in the Pointer (PTR) record.

- Publish an SPF record for your domain. SPF prevents Spammers from sending unauthorized messages that appear to be from your domain.

- Turn on DKIM signing for your messages. Receiving servers use DKIM to verify that the domain owner actually sent the message. Important: Gmail requires a DKIM key of 1024 bits or longer.

- Publish a DMARC record for your domain. DMARC helps senders protect their domain against email spoofing.

Besides the DKIM authentication method already discussed, there are more three DNS based authentication methods specifically designed for IP address and domain validation on the receiving end, which increase the likelihood that the destination SMTP server trusts you are who you say you are, and not a spammer / scammer.

These authentication methods along with strictly following mailing best practices (ex: sticking to a consistent send schedule / frequency, implementing mailing lists opt-in / unsubscribe, constantly checking blacklists, carefully building messages, etc) will help, bit by bit, to build a good sender reputation and having e-mail messages accepted and delivered to the destination users inbox.

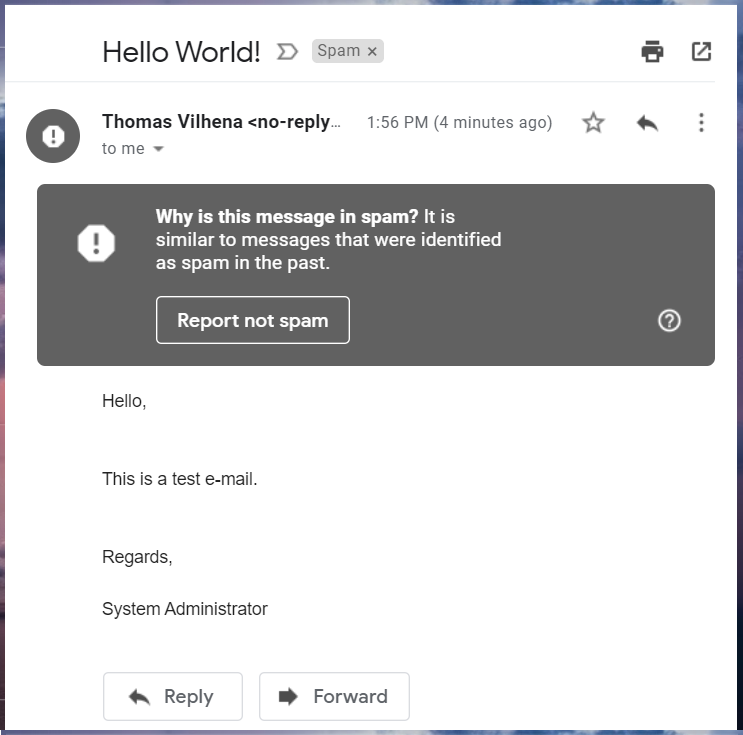

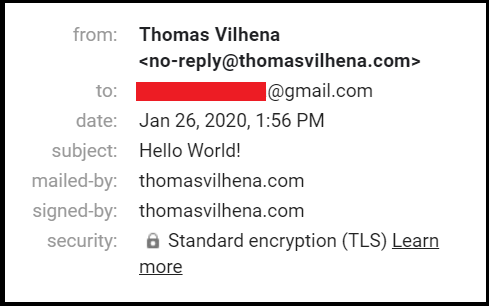

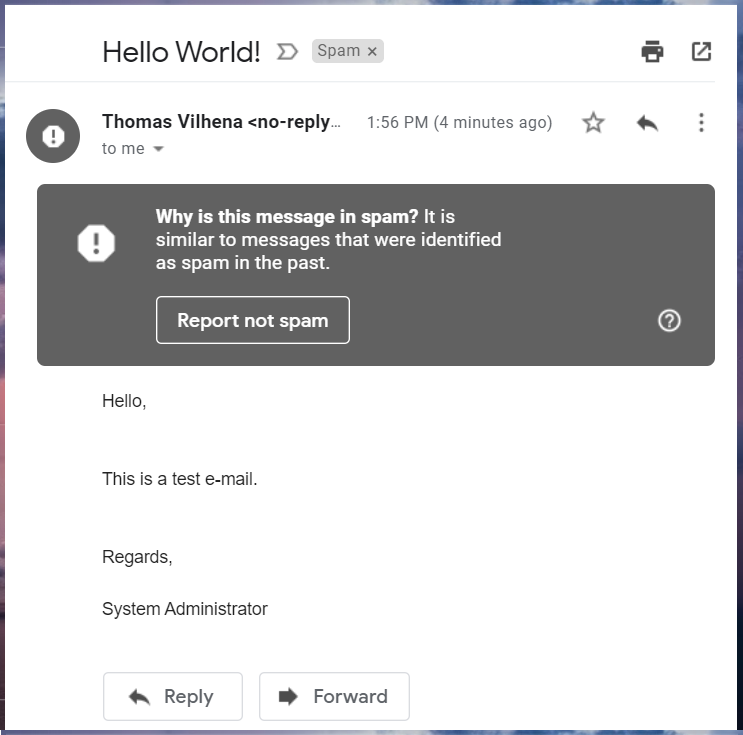

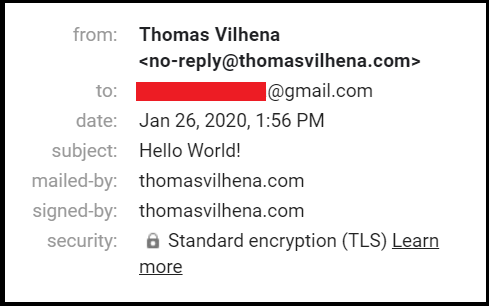

Delivery Test

This article wouldn’t be complete without a successful delivery test, so I followed the steps presented in the previous sections and:

- Created an EC2 instance running on AWS

- Created a SPF record for that instance’s public IP Address

- Generated a private RSA key for signing messages

- Turned on DKIM by creating a DNS record publishing the public key

- Ran the Mail Broker from the EC2 instance sending a “Hello World” message

This time the response from Gmail server was much more friendly:

250 2.0.0 OK 1580057800 f15si8371297qtg.4 - gsmtp

Nevertheless, since my domain has no mailing reputation yet, Gmail directed the message to the Spam folder:

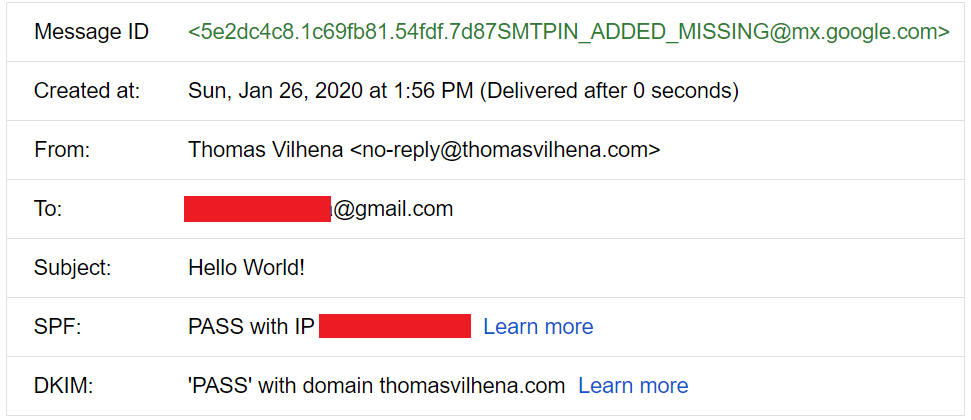

Here are the delivery details:

Notice that standard encryption (TLS) was used for delivering the message, so the connection upgrade worked as expected.

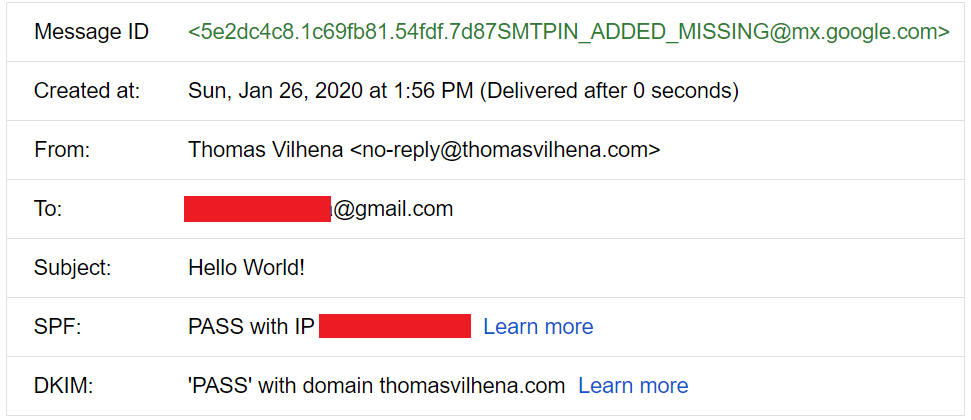

What about SPF authentication and DKIM signature, did they work? Using Gmail’s “show original” feature allows us to inspect the received message details quite easily:

Success! Both SPF and DKIM verifications passed the test ✔️

Building a mail delivery system from scratch is no simple feat. There are tons of specifications to follow, edge cases to implement and different external SMTP servers that your system will need to handle. In this experiment I only implemented the basic cases, and interacted mainly with Gmail’s server which is outstanding, giving great feedback even in failure cases. Most SMTP servers out there wont do that.

Mail transmission security has improved a lot over the years, but still has a long way to go to reach acceptable standards.

It was really fun running this experiment, but I must emphasize it’s not intended to production use. I guess I will just stick to a managed mail sending API for now 😉