Six years (so far) developing and managing the same application has taught me a few lessons, one of them being the value of pursuing system design coherence. It’s a collective, rather than an individual, responsibility, requiring the entire development team commitment.

Coherence is defined as the quality of being logical, consistent and forming a unified whole. Which from my point of view directly relates to how system design should be handled:

- Logical: System design decisions should be justified, following a clear line of thought.

- Consistent: System design decisions should be compatible, in agreement, with its current state.

- Unified whole: System components should fit together, seamlessly working alongside each other.

Below are listed five major practical guidelines on how to manage system design coherence in software projects.

1 - Create and follow codebase conventions

This is one of the most basic yet beneficial measures you can adopt to improve code quality. It deals with how source code files are written and organized within your codebase.

We developers spend most of our time reading, not writing, code, hence it’s extremely important to define and enforce coding conventions up front in your product development life cycle targeting improved code readability.

I personally adopt a combination of organizational and clean coding conventions such as:

- Segment Files/Directories/Namespaces by domain

- Avoid multiple languages in one source file

- Class/Interface names should be nouns or noun phrases

- Function names should say what they do

- Avoid too many arguments in functions

- Avoid functions with too many lines

- Replace magic numbers with named constants

- Don’t comment intuitive code

- Discard dead code

- Where to declare instance variables

- Where to put braces

- Tabs vs spaces

And the list goes on…

As a result of following conventions source code will be uniform throughout the codebase, reducing the cognitive effort for searching and reading code files.

2 - Implement clear software architectures

The definition of software architecture is still a topic of debate, but there’s a general understanding that it deals with how software is developed both in terms of its physical and logical structure.

The codebase of a software project that doesn’t follow a clear architectural style, whatever it may be, deteriorates gradually as new, unstructured code is added to it, becoming harder to modify. Hence the importance of putting in the hours for the design and conservation of an adequate software architecture.

Unfortunately there isn’t a magic architecture that fits all use cases. You need to take into account several factors from your project for choosing the right path to follow.

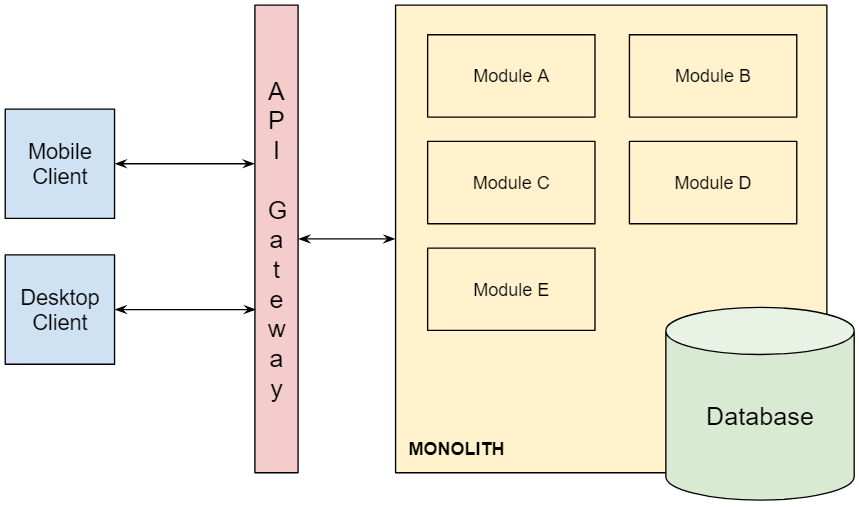

To provide a couple of examples the monolithic architecture was standard a decade ago, before the microservices architecture gained traction. Like any other, it has several benefits and drawbacks, to name a few:

Pros:

- Shared Components: Monoliths share a single code base, infrastructure and business components can be reused across applications, reducing development time.

- Performance: The code execution flow is usually constrained to a single process, making it faster and simpler when compared to distributed code execution.

Cons:

- Tight Coupling: Code changes to shared components can potentially affect the whole system so it has to be coordinated meticulously.

- Scalability: You cannot scale components separately due to interdependencies, only the whole application.

A software team working on a product that deals with complex data models and needs processing operations to be fast, performant and integrated may prefer to go for a monolithic application.

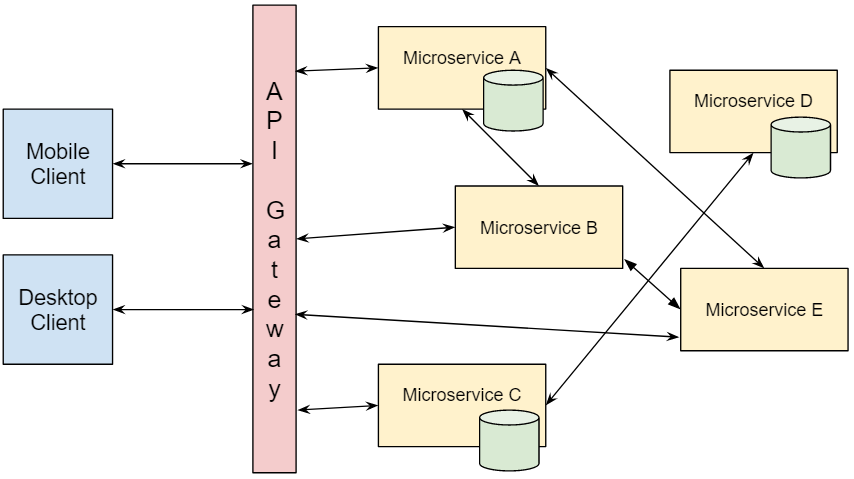

On the other hand the microservices architecture addresses many of the situations in which monoliths fail, being a great fit for distributed, large scale web applications:

Pros:

- Decoupled: The application can remain mostly unaffected by the failure of a single module. Also, code changes in one microservice wont impact others, providing more flexibility.

- Scalability: Different microservices can scale at different rates, independently.

Cons:

- DevOps: Deploying and maintaining microservices can be complex, requiring coordination among multiple services.

- Testing: You can effectively test a single microservice, but testing a distributed operation involving multiple microservices is more challenging.

Some architectural patterns are more concerned with the physical disposition of an application and how it’s deployed than with its logical structure. That’s why it’s also important to define a clear logical architecture to guide developers on how to structure code, so that everyone in your team understands how components talk to each other, how responsibility is segregated between modules, how to manage dependencies and what the code execution flow looks like.

3 - Fewer is better: Languages, Frameworks and Tools

With each additional language, framework and tool you introduce into your system comes an additional development and operational cost. This cost comes in different forms, which are illustrated in the following examples:

a) You are a member of development team highly experienced in Nginx + Python + PostgreSQL web applications. The team is fluent in this stack, the development pipeline is tidy and new features are delivered frequently. Then one day a developer decides to implement a new strategic feature using a different stack, say Apache + Java + MySQL, in which he is also highly experienced, but his colleagues aren’t. Now whenever this developer is busy and his colleagues have to implement a feature using the different stack they do so more carefully, since they aren’t quite familiar yet with all the programming language features, web server and database modes of operation, etc, as they are with the original stack. Thus, development time increases.

b) You have been assigned for managing a production environment of an application facing a considerable growth rate. Your goal is to deliver a SLA of 99.9% avaiability, which breaks down to only 8h of downtime per year. You gather the team to evaluate all technologies and plan the infrastructure required to support the growth rate: health checks, operational metrics, failure recovery, autoscaling, continuous integration, security updates. The plan is implemented and you start fine tuning the production environment, dealing with unforeseen events and issues. After much effort the production environment is stable and on its way to deliver that SLA, but you discover that a different tech stack was introduced and needs to be deployed. You’ll need to reevaluate the infrastructure. Also if the stack isn’t compatible with your current hosting environment it will potentially incur additional operational expenses.

These are just two illustrative situations, showing the impact of adopting additional technologies on development productivity, infrastructure complexity and operational expenses.

Of course, different technologies bring different possibilities. If we were to use only a limited set of technologies life as a developer would be much harder. For instance, there are scenarios where graph databases outperforms relational databases immensely. In these scenarios the choice is easy since the benefits outweighs the costs. The point is, you should always evaluate the long-term costs of a technological decision before making it to solve a short-term problem.

All right, but how does this relates to system design coherence?

Well, I believe that a system that is designed to avoid redundant technologies, that takes most out of its current stack, that has a stable production environment, whose team carefully evaluates structural changes and is able to sustain development productivity in the long run is a system that is clearly following the definition of “coherence”.

4 - Involve your team in system design decisions

As I’ve stated in the beginning of this article system design is a collective, shared responsibility. Individual, local actions have the potential to affect the system globally, so it’s essential that the development team is on the same page regarding the codebase conventions, employed architectures and the technology stack.

The most effective way to build this shared knowledge environment is to involve the team in system design decisions. The benefits are plenty:

- Individuals feel valued and part of the team

- Important decisions are challenged by the entire team before being made

- System design strengths and weaknesses are more clearly understood by everyone

- Creates a sense of collective accountability and trust

This doesn’t mean that every developer on the team should have equal decision power. Senior roles should certainly have more influence in decision making then junior roles. But it’s vital that everyone has the opportunity to give his opinion and participate. Less experienced developers will definitely grow from these proceedings.

At the same time the team must be aware of the productivity costs that arise when time is needlessly spent arguing about minor, trivial decisions. Optimize for speed, and focus on moving forward and delivering results rather than overcaring for details.

5 - The All-in rule

Efforts to refactor a system design should be conducted to completion (all-in), rather than being partially concluded. There’s a great risk of eroding your system design if developers feel free to apply different coding styles and architectural patterns locally whenever they see fit. Before too long you will end up with a disconnected, sometimes conflicting, system design.

By preserving your system design you’re also preserving the validity of your team’s shared knowledge about the system, which is extremely valuable. During development we make several assumptions on the behavior of the system based in this shared knowledge. Once it starts to lose validity unexpected issues start occurring, developers become justifiably less confident in the system design, implement features more carefully, losing productivity.

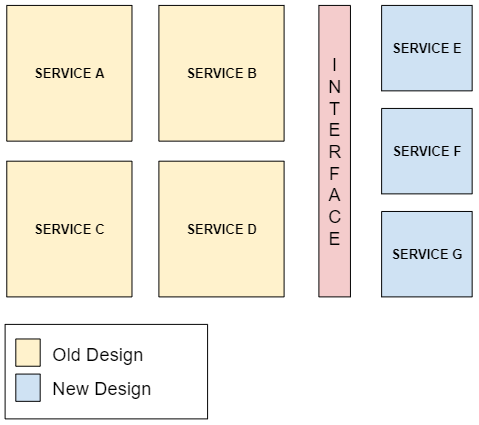

The challenge here is being open to improve your system design knowing that it can be exceptionally expensive to conduct a large system refactor up to completion. An approach I have used in a similar situation was to isolate refactored services behind an integration interface. The result was two independent system designs seamlessly working alongside each other, rather than having them mixed together:

These five guidelines have served me well over the past years, helping to keep productivity high, optimize resources and deliver up to the standards. It’s more a mindset than an actual process. Like all mindsets it should be constantly challenged and subject to improvement.