Third-party module integration has become a frequent task in application development, allowing developers to leverage functionality quickly for implementing what matters most, business logic.

Usually it comes in two forms:

- Software Packages

- Web-based API

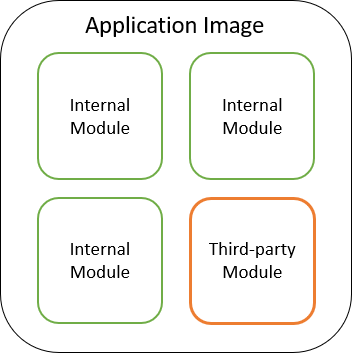

A third-party software package is composed of library files and data files which are executed by applications locally, and become part of the application’s deployable image:

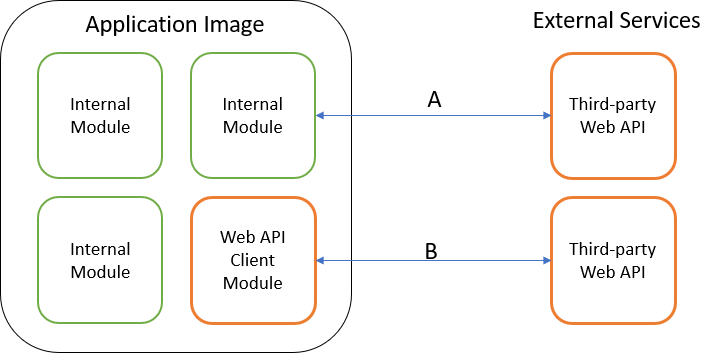

A web-based API (Application Programming Interface) provides a set of functionalities which, when consumed, are executed externally from the application, in another process or in a remote server. The application can consume the web API directly with the assistance of network libraries (A), but more often client side software packages are provided for handling communications between the two parties (B):

The next section covers the dependency management challenge that arises when integrating third-party modules into applications.

Dependency Management

Integrating with external modules can be treacherous, since it’s easy to fall into the trap of referencing it’s classes (or APIs) directly from business logic classes, producing tightly coupled code. One property of coupled code is that it’s resistant to change, making it difficult to deal with change requirements, package updates or replacing third-party modules altogether.

Hence, there’s a need for a module dependency management approach that protects business logic from coupling with external code, improving application’s flexibility and overall architecture. This is achieved by applying the Dependency Inversion principle, which dictates that “one should depend on abstractions, not concretions”.

What's an abstraction?

Simply put, an abstraction is a contract describing how a functionality is served, it’s an internal API. High level programming languages even have a keyword for defining abstract classes, which will not be covered in this article. Instead, we will focus on interfaces, which also allow for the abstraction of functionality implementation.

For instance, consider the following simplified interface:

public interface BankAccount

{

string GetBankName();

AccountNumber GetAccountNumber();

double GetBalance();

Statement[] GetStatements(DateTime start, DateTime end);

void Withdraw(double amount);

void Deposit(double amount);

}

An interface only defines methods signatures and input/output parameters, but doesn’t implement them. Even so, when properly defined, just by looking at it we naturally know what to expect when calling the interface’s methods, because the interface is implying expected behaviors.

Going further, we can extend this simple abstraction by applying the Factory pattern to deal with the problem of instantiating objects without knowing the exact class of the object that will be created:

public interface BankAccountFactory

{

BankAccount GetBankAccount(AccountNumber accountNumber);

}

It may seem counter intuitive now how a factory class can create an objetc whose type is still not known, but the next section will shed some light into this.

What's a concrete implementation?

In this context a concrete implementation is the defacto class implementation of an interface. From the example above it’s reasonable to imagine BankAccount implementations for various banks:

public class BankOfAmericaAccount : BankAccount

{

/* ... */

}

public class ChaseAccount : BankAccount

{

/* ... */

}

public class WellsFargoAccount : BankAccount

{

/* ... */

}

Each one of these illustrative classes would be dependent on a third-party module from the underlying bank for implementing interface behaviors.

Then, the factory interface implementation would be responsible for instantiating the appropriate bank account object from an AccountNumber, according to the bank it belongs, for instance:

public class USABankAccountFactory : BankAccountFactory

{

public BankAccount GetBankAccount(AccountNumber accountNumber)

{

switch (accountNumber.BankCode)

{

case BankCode.BankOfAmerica:

return new BankOfAmericaAccount(accountNumber);

case BankCode.Chase:

return new ChaseAccount(accountNumber);

case BankCode.WellsFargo:

return new WellsFargoAccount(accountNumber);

default:

throw new NotImplementedException();

}

}

}

How to resolve business logic abstract dependencies?

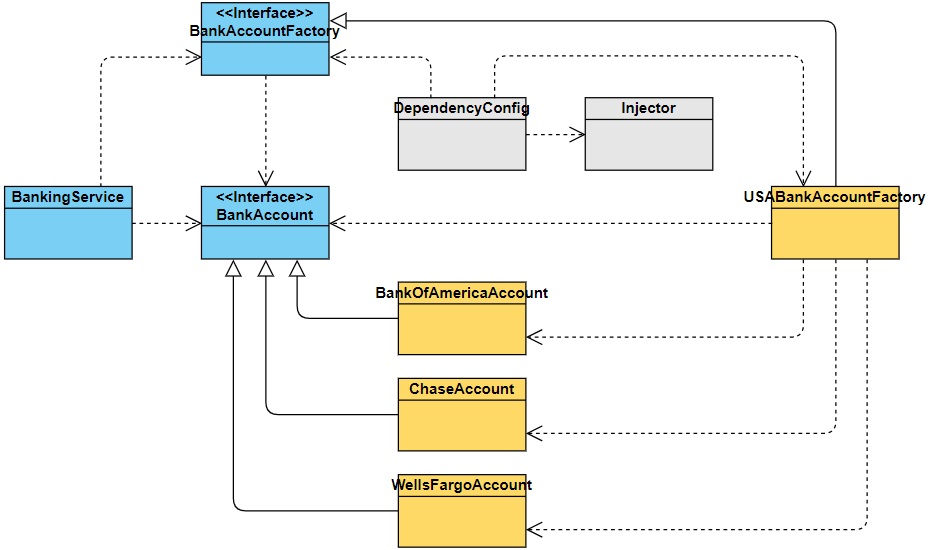

Now the dependency inversion principle kicks in. The interfaces concrete implementations are injected into business logic objects with the help of a dependency injection (DI) framework. The DI framework will incorporate all dependencies into itself, using them to construct application services, which aren’t dependent on any external module:

Each color in the class diagram above represents a different section of the whole system. In blue the application’s business logic. In dark yellow the interfaces concrete implementations which are dependent on third-party modules. Finally in grey the DI related classes, one from the DI framework (Injector) and the other responsible for configuring the application dependency graph (DependencyConfig).

Notice that application business logic is completely isolated from external modules. However, the application is dependent on the DI framework, and it won’t be able to instantiate service classes (such as the BankingService) without it. Some may say that the dependency on the DI framework defeats it’s very own purpose, but for large applications the benefits largely outweighs this drawback. If one is careful enough to avoid complex DI frameworks and use only what’s strictly required for isolating business logic from third-party modules then this self-inflicted dependency should not be a problem at all.

DI Framework Configuration

There are several approaches for configuring an application’s dependency graph. Two of the most common are by using XML files which maps concrete implementations to interfaces, or by defining a configuration class for mapping dependencies in code, for instance:

public class DependencyConfig

{

public static void RegisterDependencies()

{

using (var injector = new Injector())

{

injector.AddTransient<BankAccountFactory, USABankAccountFactory>();

}

}

}

The “Transient” suffix means whenever a dependency is resolved a different object is instantiated. Other commonly supported life-cycle models are “Singleton” for always resolving a dependency with the same object and “Scoped” for associating the lifetime of the object with the duration of a web request or network session.

This configuration method is then called in the application’s uppermost layer (ex: presentation layer) initialization, allowing subsequent calls for creating services during runtime:

using (var injector = new Injector())

{

var bankService = injector.GetService<BankService>();

}

The illustrative BankService will be allocated and it’s dependencies (magically) resolved:

public class BankService

{

public BankService(BankAccountFactory factory)

{

this.factory = factory;

}

/* ... */

}

In the example above the BankService is using constructor based injection, which is one of several injection styles handled by DI frameworks.

This is one of several software engineering techniques that when combined allow for the effective and continuous development of large applications.

Stay tuned for more 🤓