If you follow the crypto market, you may already be familiar with the strong direct correlation between cryptocurrencies prices, native or tokenized. When BTC goes down, pretty much everything goes down with it, and when BTC is up, everything is most likely to go up too. This correlation isn’t exclusive to BTC, impacts on the price of many other cryptocurrencies (such as ETH) also reverberate across a wide range of crypto assets, with different degrees of strength among them.

Have you ever asked yourself why is it so? One straightforward answer is that large events impacting the price of BTC (or other crypto) will make crypto investors want to assess their exposure not only to BTC but to other crypto assets in a similar manner. This answer is intuitive, but mostly behavioral and hard to quantify. However, there are other structural sources of correlation between cryptocurrencies that are often overlooked, and in this post I analyze one of them: Decentralized exchange (DEX) pairs.

DEX pairs

A DEX pair, popularized by Uniswap, can be viewed as a component in the blockchain that provides liquidity to the crypto market and allows wallets to trade between one asset and another in a decentralized way. For instance, the BTC/ETH pair allows traders to swap between these two currencies in either direction. Likewise, the BTC/USDC pair allows traders to exchange bitcoin for stablecoins, and vice-versa.

And how do DEX pairs build-up correlation between cryptocurrencies? To answer this we need to dive a bit into how DEX pairs work:

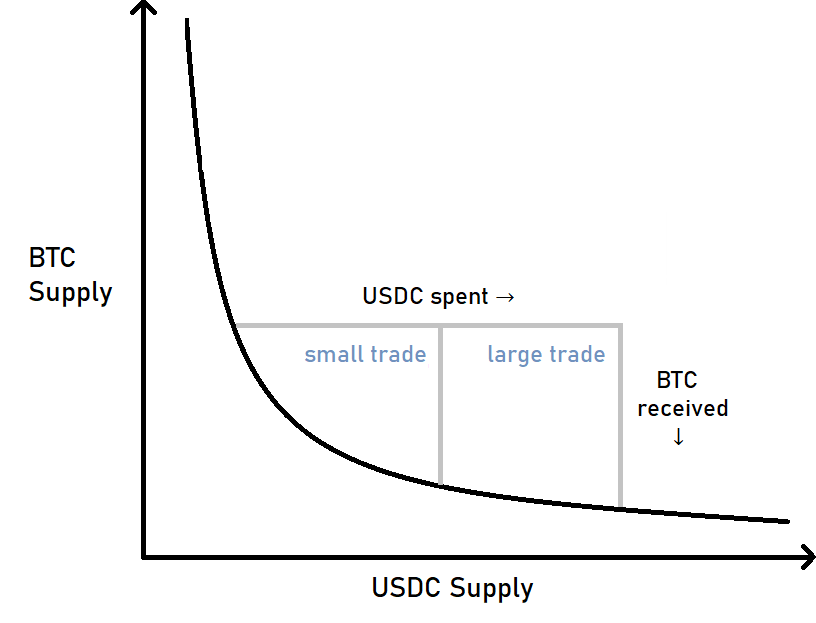

First, in order to provide liquidity a DEX pair needs to have a reasonable supply of both of its tradable assets. Then it implements a mathematical formula for calculating the exchange rate between these two assets honoring the supply/demand rule, i.e., the more scarce one of the assets becomes in the DEX pair’s supply, the more valuable it’ll be in relation to the other asset.

Second, the sensitivity of the exchange rate in a DEX pair will depend on the total value locked (TVL) in its supply. Each trade performed against the DEX pair changes the relation of its assets, thus changing the effective exchange rate for succeeding trades. The higher the TVL, the less sensitive the exchange rate will be with regard to the trade size.

Implications on correlation

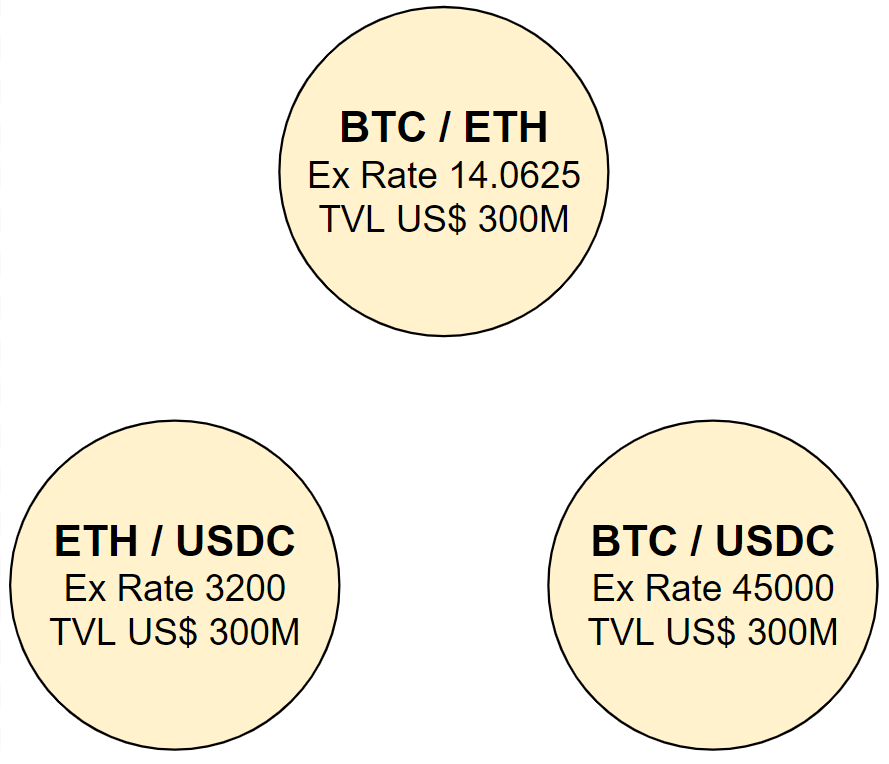

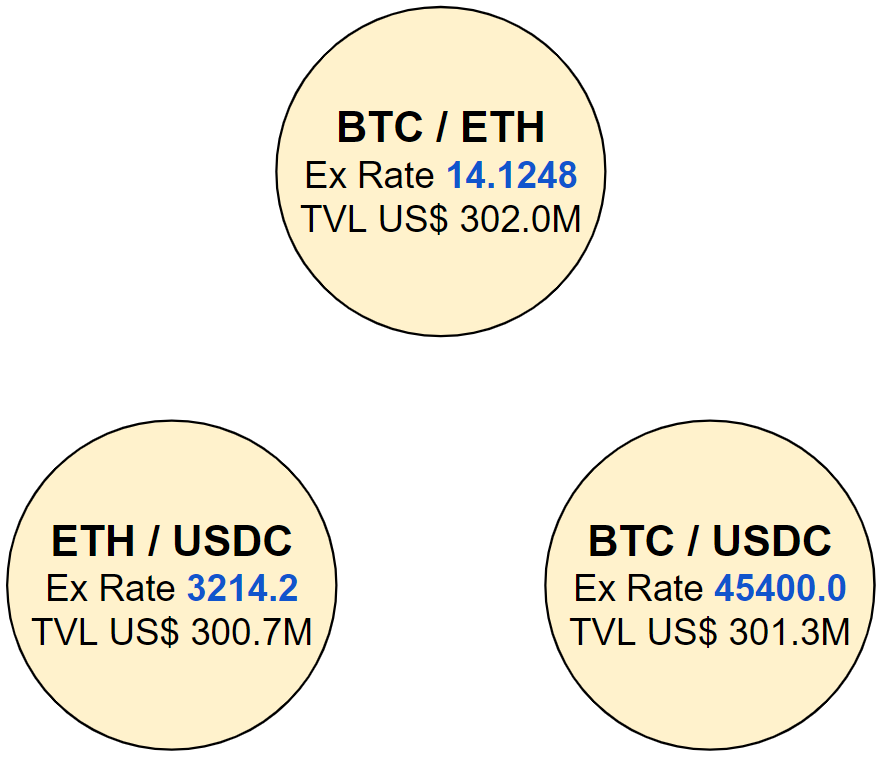

Now we can start exploring the implications on correlation. You see, a DEX pair is basically a bag which locks pairs of cryptocurrencies supplies together, creating a hefty relationship between them. Even so, if you have one or two DEX pairs to play with you may not achieve much with respect to correlation of the assets prices against the dollar. But if we define a closed system with at least three DEX pairs like the one shown below, interesting things start to happen:

In this system we have:

- One BTC/USDC pair defining a price of US$ 45k per BTC

- One ETH/USDC pair defining a price of US$ 3.2k per ETH

- One BTC/ETH pair creating a relationship between these two assets

- Pricing consistency between all pairs

- US$ 300M TVL in each pair

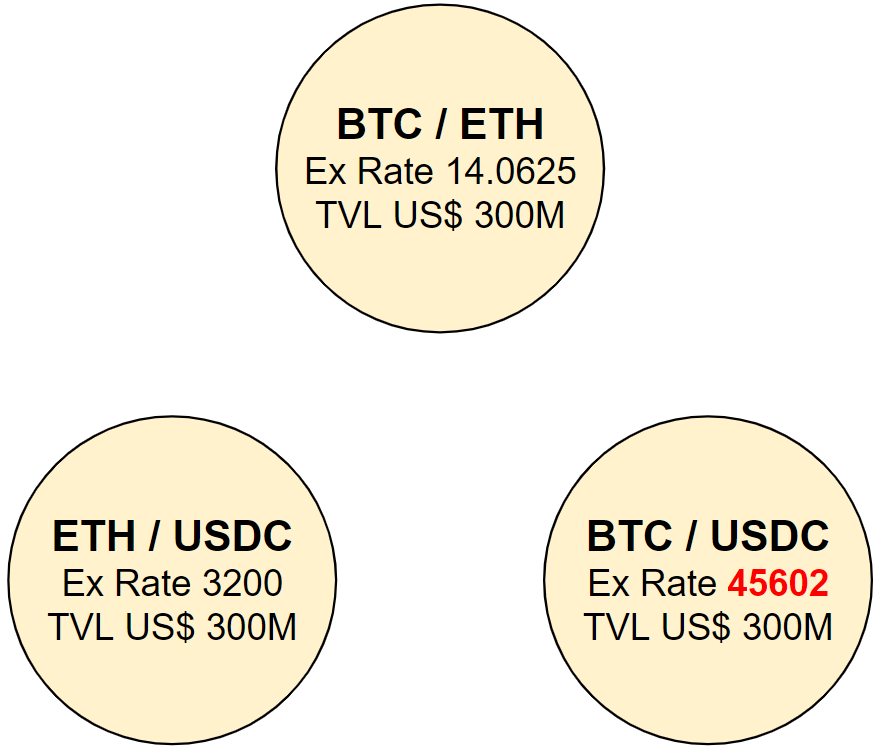

Remember that each DEX pair defines an independent exchange rate between two assets. Then, if we buy a lot of BTC in the BTC/USDC pair with stablecoins, for instance a US$ 1M trade, we’ll generate an upwards pressure in the price of BTC as defined by that pair:

Trade details:

- 1M USDC input

- 22.075 BTC output

- Effective Ex. Rate of 45300

- Resulting BTC/USDC pair Ex. Rate of 45602

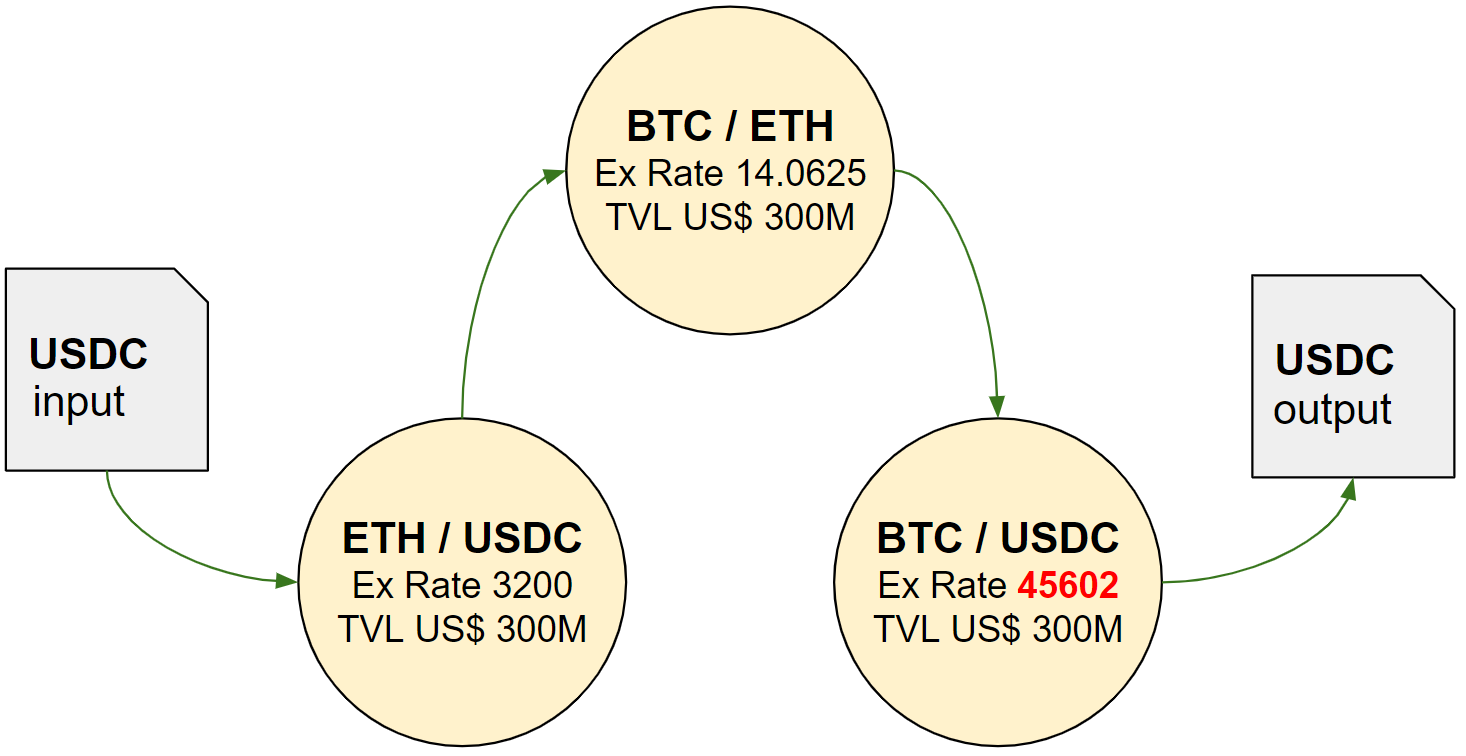

This new price will be unbalanced in regards to the other pairs, triggering an arbitrage opportunity since a trader holding USDC could now buy ETH in the ETH/USDC pair, exchange ETH for BTC in the BTC/ETH pair and finally sell BTC for stablecoins in the BTC/USDC pair making a profit.

Now let’s consider that a trader took advantage of this arbitrage opporutnity to the fullest and analyze the resulting exchange rates when the system reaches equilibrium:

So, comparing to the initial state of the system, the US$ 1M trade to buy BTC had the effect of:

- Rising the price of BTC by 0.89% (from US$ 45,000.00 to US$ 45,400.00)

- Rising the price of ETH by 0.44% (from US$ 3,200.00 to US$ 3,214.20)

- Inflating the TVL in the system by 0.44% (from US$ 900M to US$ 904M)

As you can see, the initial rise in the BTC price opened up an arbitrage opportunity that once explored to exhaustion had the effect of rising the price of ETH as well. To put it simply, this closed system created an inherent correlation between ETH and BTC prices.

Conclusion

In this qualitative analysis we’ve seen how a system of DEX pairs builds-up correlation between crypto assets as a result of exploring arbitrage between these pairs. Even though the analysis was based on a simulated US$ 1M trade to buy BTC, similar and consistent results hold for selling BTC, as well as for buying/selling ETH, within this closed system.

As of the time of this writing Uniswap on Ethereum mainnet alone holds US$ 4.77b of TVL in hundreds of DEX pairs, creating an entangled net of relationships between crypto assets and contributing to the correlation among them.

Notes

-

The simulation whose results are presented in this post was based in Uniswap’s V2 protocol implementation. Similar results should hold for the more complex and recent V3 implementation which adopts the concept of virtual supplies.

-

The complete source code for running this simulation is provided on GitHub. The routine used for generating the results presented in this post can be found in this code file.