The semantic URL attack is one of the most popular attack types aimed at web applications. It falls into the wider “broken access control” category and has been consistently listed amongst OWASP top 10 application’s security risks lists 1.

In it an attacker client manually adjusts the parameters of an HTTP request by maintaining the URL’s syntax but altering its semantic meaning. If the web application is not protected against this kind of attack then it’s only a matter of the attacker rightly guessing request parameters for potentially gaining access to sensitive information.

Let’s take a look at a simple example. Consider you’re an authenticated user accessing your registered profile in a web application through the following URL:

https://domain.com/account/profile?id=982354

By looking at this request URL we can easily spot the “id” parameter and make an educated guess that it most likely represents the internal identifier of the requesting user. From that assumption an attacker could then try forging accounts identifiers for accessing their profile information:

https://domain.com/account/profile?id=982355

If the web application isn’t properly implementing a protection against this type of attack through access control then its users data will be susceptible to leakage. The attacker could even make use of brute force for iterating a large number of “id” guesses and potentializing his outcome.

Two frequently adopted (but insufficient!) countermeasures for minimizing risks in this situation are:

- Use of non sequential IDs for identifying users

- Throttle users web requests to the application

The first one makes guessing valid users (or other resources) IDs much harder, and the second one prevents brute force attacks from going through by limiting the amount of requests individual users can make to the application. However, none of these measures solve the real problem, they’re only mitigating it! It will still be possible to access or modify thrid parties sensitive data by making the right guess for the request parameters.

So what’s the definitive solution to this problem? As we’ll see in the next section one strategy is for the web application to implement an access control module for verifying the requesting users permissions for every HTTP request he/she makes, without exception, for properly protecting against semantic attacks.

Filtering Requests

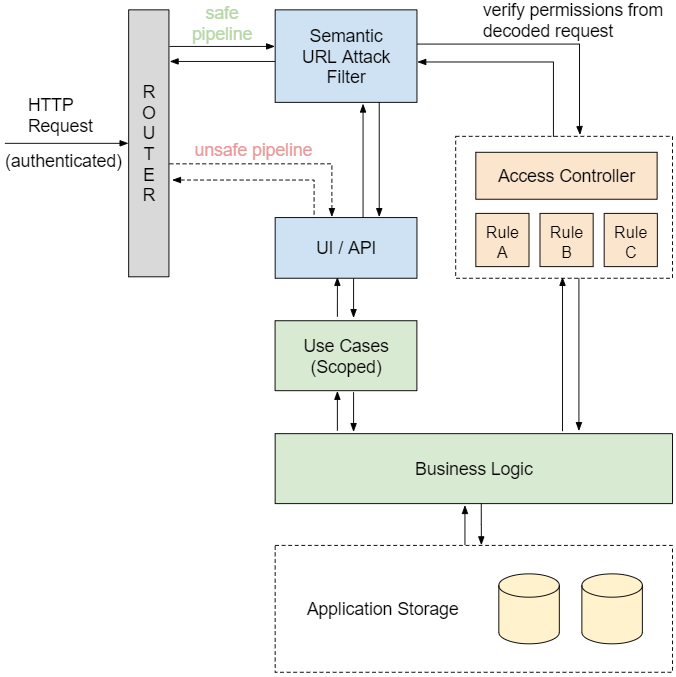

In essence a web application that’s susceptible to semantic URL attacks isn’t filtering HTTP requests as it should. Consider the generic web application diagram below:

An authenticated HTTP request arrives at the endpoint and is routed for processing. Without filtering (“unsafe pipeline”) the request goes directly to the application UI / business logic for processing, accessing its storage, and returns unverified data to the caller. With filtering (“safe pipeline”) before the request is actually executed a verification is performed for making sure it’s authorized to execute in the first place.

The semantic URL attack filter will be responsible for decoding the request’s URL, its parameters, and performing necessary verifications on whether or not the requesting user is allowed to access the resources mapped by these parameters. A typical design includes an “access control” module that implements resource specific verification rules for querying the request caller’s permissions on the set of affected resources. These rules can be independent of each other in the case of non related components, but they can also be constructed as a combination of lower level rules for more elaborate resources. For successfully validating a web request the semantic URL attack filter must execute all pertinent access control rules based on the decoded web request.

As you can evaluate from the diagram the request filtering and access control logic are completely decoupled from the application presentation and use case layers. Request filtering will occur prior to the execution of use cases. This allows for an effective segregation of responsibilities, making each component’s logic more clear and concise.

But there’s a catch. Since security verification is performed externally to the application business logic, all application use cases should be scoped, i.e, internal commands and queries must be designed for reducing the request’s footprint to the minimum required for it to be successfully executed without compromising sensitive data, otherwise the whole request filtering procedure would be deemed useless.

Performance Considerations

The proposed design brings in a few performance considerations. Since access control logic is decoupled from use case logic requests will incur at least one additional database round-trip for fetching data required for performing security verification. In more complex cases in which the request is accessing several resources this could mean multiple additional database round-trips. To mitigate this performance drawback two techniques can be employed i) caching and ii) hierarchical security.

Caching of users resource permissions can be based on resources unique identifiers. An appropriate cache invalidation strategy should be adopted according to the application security requirements to prevent users from holding resource permissions that may already have been removed. A sliding cache expiration policy may be adequate for expiring cache entries for an authorized user only when said user becomes inactive, improving overall performance.

Hierarchical security comes into play for reducing the amount of resources whose access permissions need to be evaluated. The concept is simple, if an user holds access permissions to a “parent” resource then, since application use cases logic is scoped, we can expect this user to have at least the same level of access permissions on the resource’s “children” without really having to perform this verification.

In closing, it is important to emphasize that a key requirement of the presented protection strategy is that developers only implement scoped use cases. All developers should be aware of this requirement while coding. Hence, code review will be particularly important for not letting security vulnerabilities go through to the master branch of the codebase.

Sources

[1] OWASP. Top 10 Application Security Risks - 2017

[2] Wikipedia. Semantic URL attack