There’s a general piece of wisdom in database adminstration that goes like this:

In order to reduce lock contention in the database, a database transaction has to be as short as possible.

And it holds, 99% of the time. However, I recently found myself in that 1% when I tried to solve a database locking problem blindingly optimizing a transaction duration, only to realize later that I was actually adding fuel to the fire 🔥

The Problem

In our mobile application users recurrently receive tasks, mostly surveys, which they participate sending us back their answers. On average tasks range from 500 to 1000 users, but it’s not unusual for us to submit a task to 10k or more users at a time.

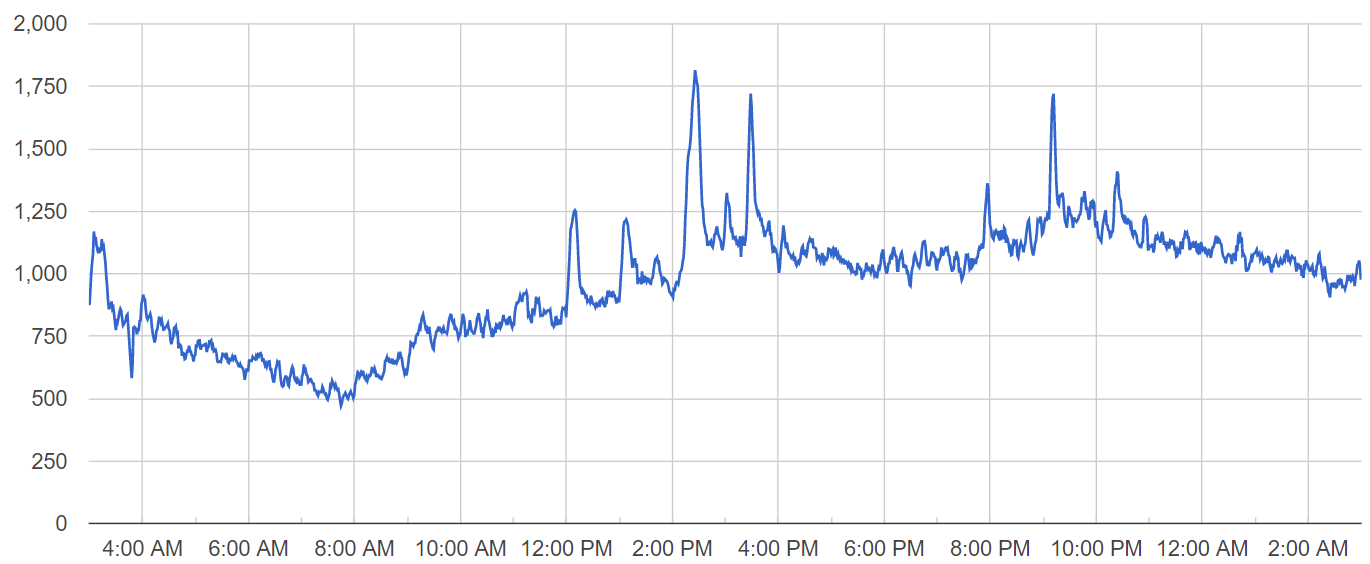

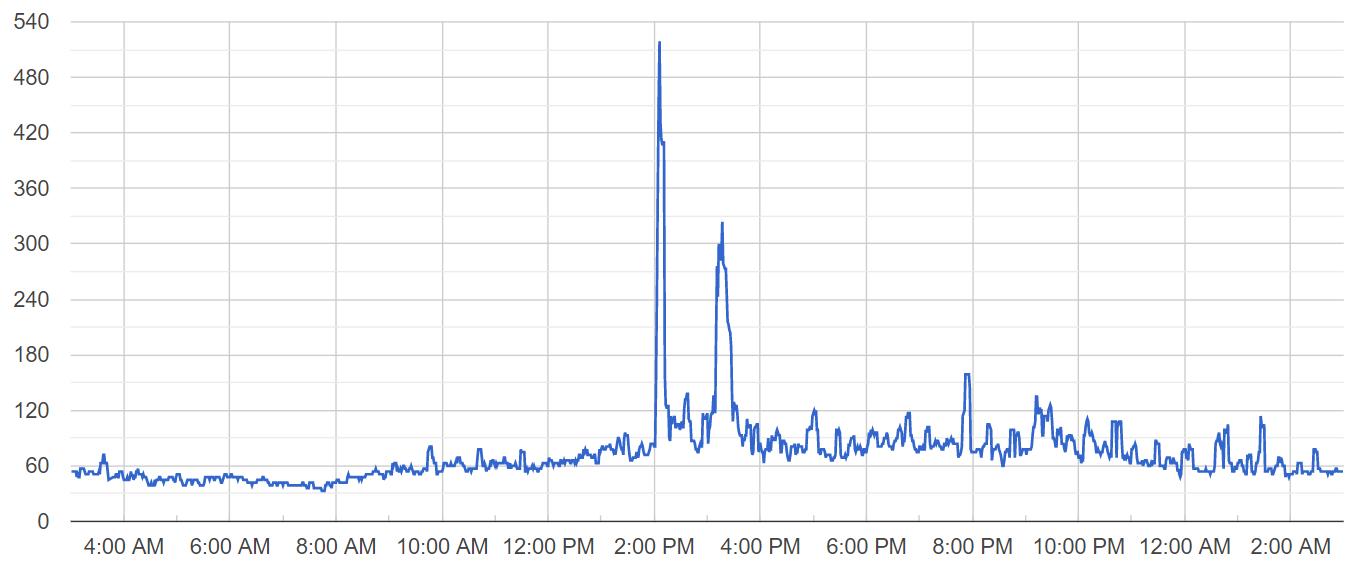

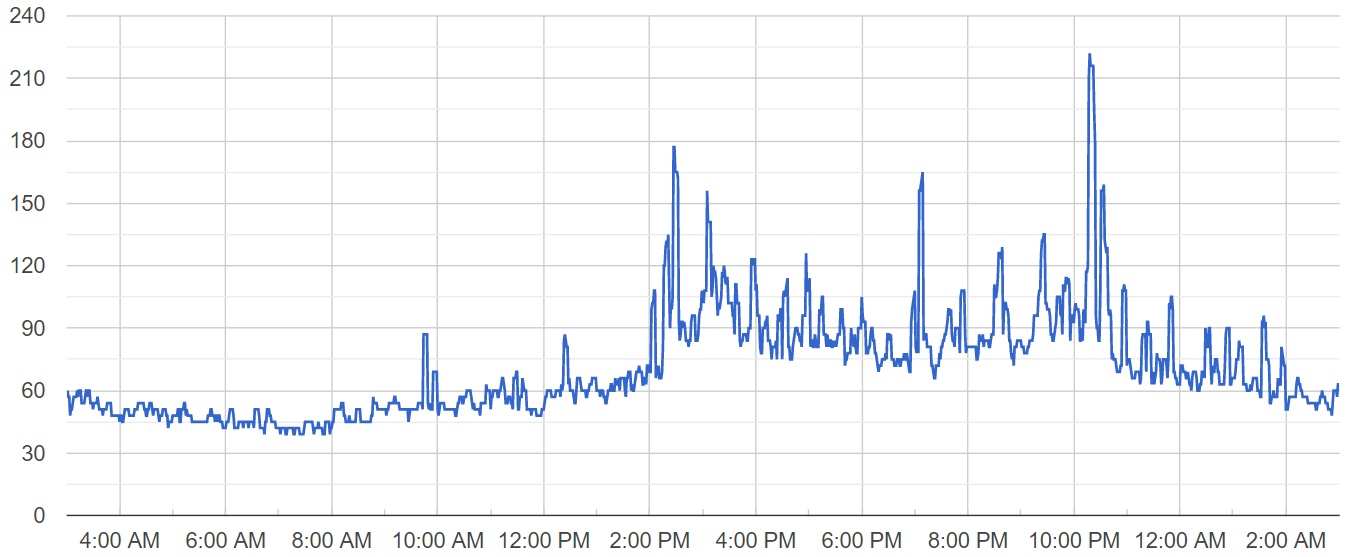

Tasks are delivered to mobile users in a single batch, causing spikes in the number of active users throughout the day. The chart below displays the number of online users at one of our servers on a day when the problem occurred:

Notice three major activity spikes at 2:25 PM, 3:28 PM and 9:11 PM regarding three tasks that were submitted to our userbase. Now let’s analyze the chart of active database connections for that server on the same day:

There were two worrying active database connection spikes right before the first two user activity spikes, one at 2:05 PM and the other at 3:12 PM.

While the number of active users grew 2x, the number of active database connections grew 6x, which for me was a red flag worth dealing with.

Investigation

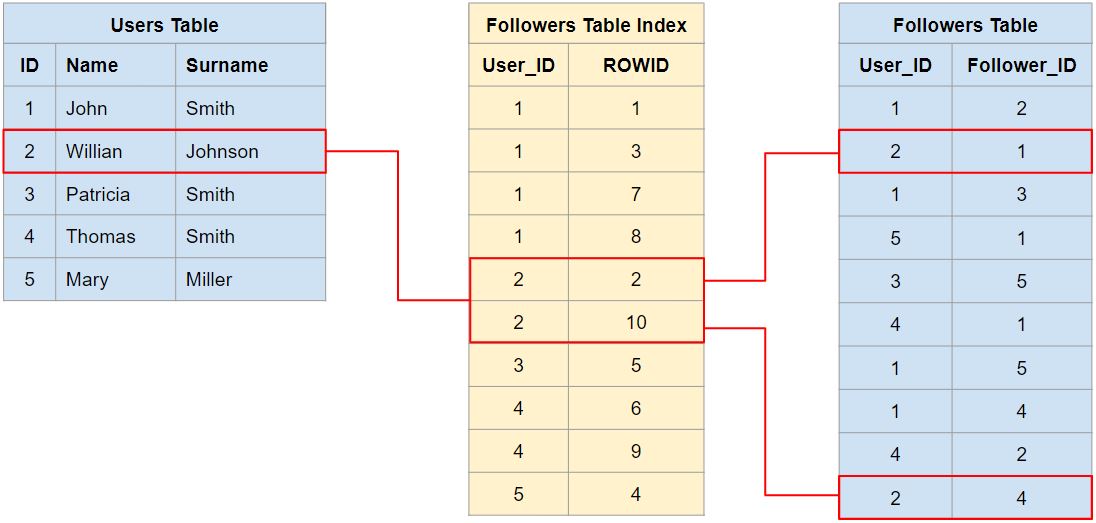

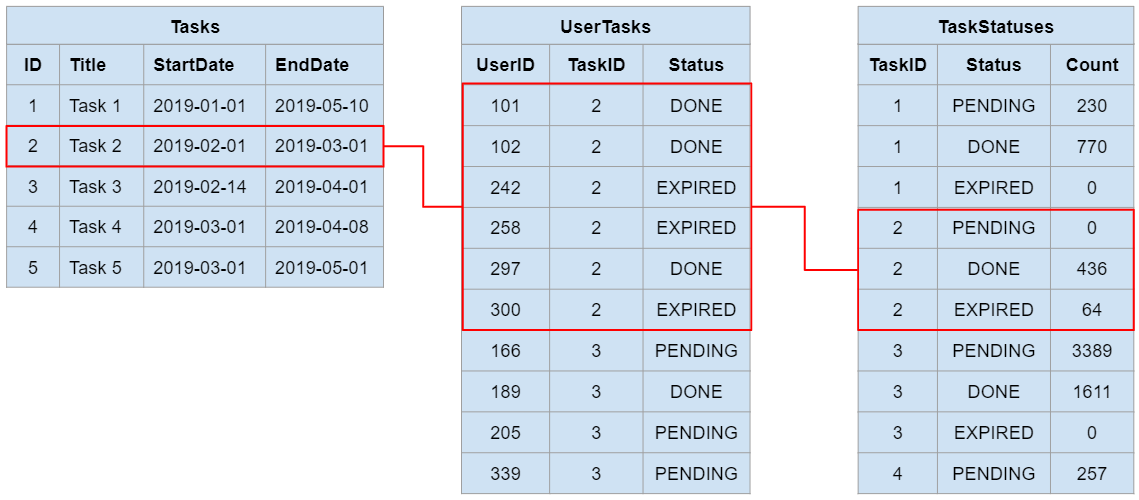

From the database adminstration logs it was easy to spot that this was a locking escalation problem. There are at least three database tables relevant for delivering tasks to our mobile users. A simplified representation is provided below:

- Tasks: This table contains all tasks and their details such as title, start date, end date, etc

- UserTasks: This is a many-to-many relationship table between users and tasks, defining which tasks each user is requested to perform

- TaskStatuses: This is an aggregation table for summarizing the statuses of each task without running a “group by” query on the “UserTasks” table

The database logs showed that a large number of queries against the “TaskStatuses” table were blocked by the task submission transaction, which often runs for a couple of minutes, and performs the following procedure:

- Creates a task by inserting it at the “Tasks” table

- Inserts empty statuses rows in the “TaskStatuses” aggregation table

- Selects eligible users for receiving the task

- Inserts an entry in the “UserTasks” table for each eligible user

- Updates the aggregation table “TaskStatuses” accordingly (using a database trigger)

The blocked queries were trying to update the “TaskStatuses” table after a user submits his answers to the task (in a serializable transaction), decrementing the “PENDING” count and incrementing the “DONE” count.

The (wrong) Solution

A straight forward approach that I tried was to breakdown the task submission into smaller batches, instead of submitting the task to all users at once, after all, several short transactions are better than one long running transaction, right?

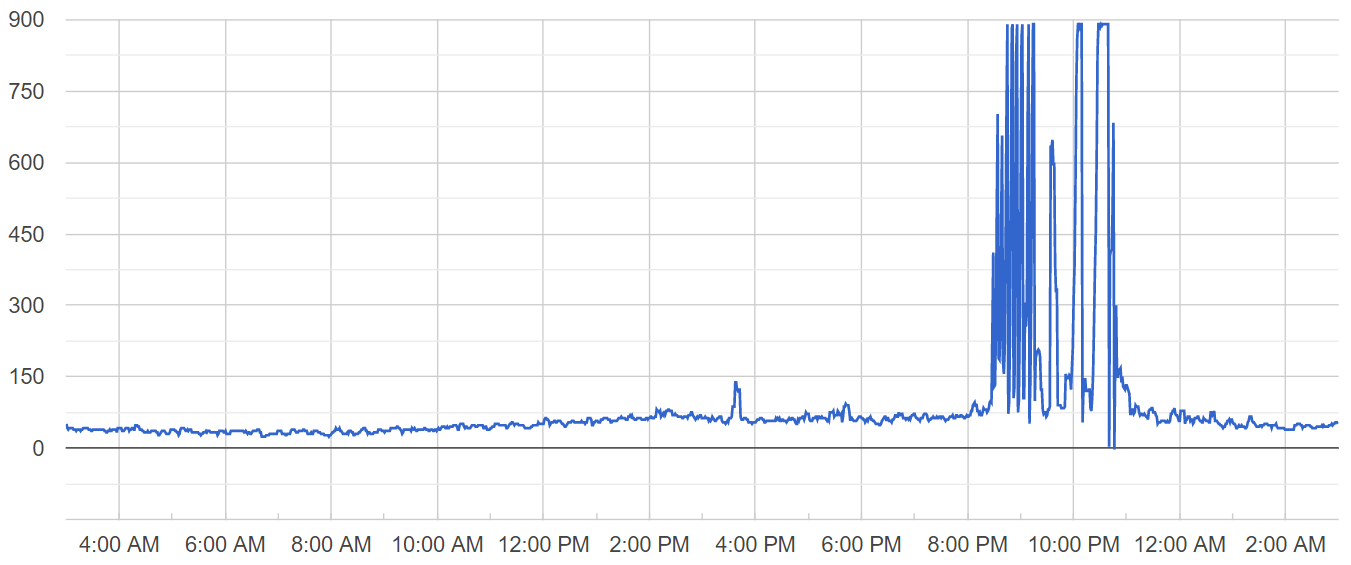

Wrong! Well, at least for my specific use case 🧐. Even though staging tests showed that there was no significant change in the overall duration of tasks submission to mobile users, on the production environment this solution backfired:

Spikes became much more frequent and “taller”. Needless to say that I had to revert this deployment shortly after applying it. Somehow splitting the longer transaction into several short transactions resulted in more frequent and vigorous locking.

Back to Investigation

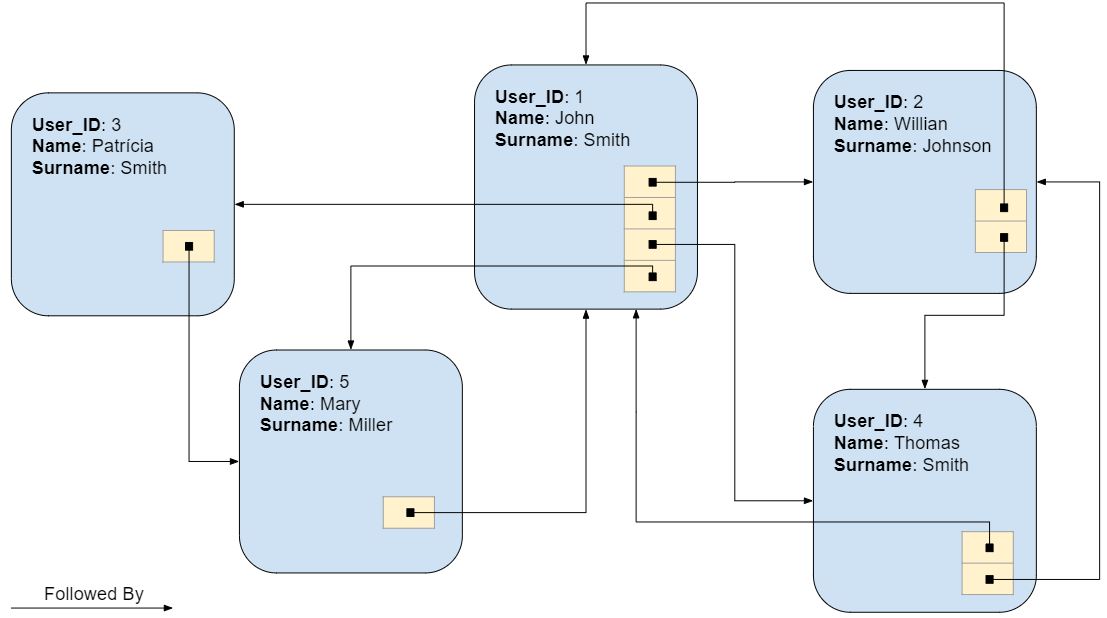

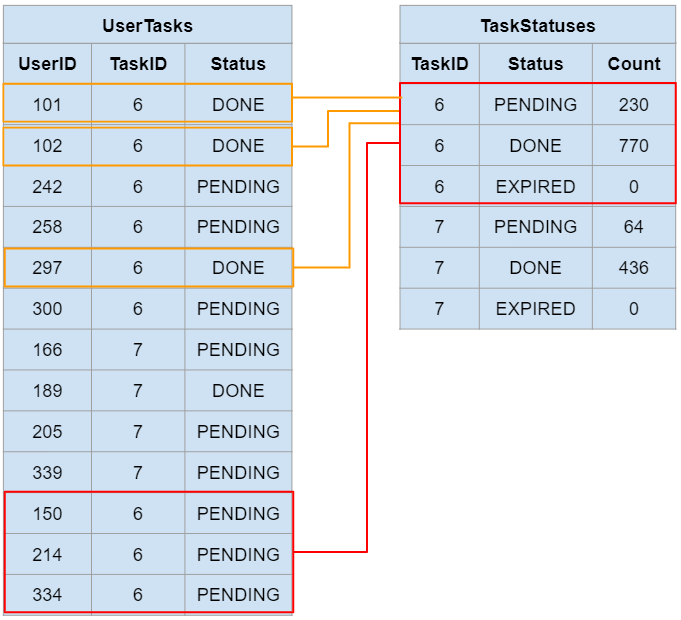

What I missed to realize while investigating this problem was that locking was escalating only for tasks that already existed, and were being submitted again to a new group of users, usually because it wasn’t possible to reach the desired number of answers from the first submission alone.

In short, the task resubmission acquired a lock for all “TaskStatues” rows for that task, the same rows that are updated when users individually submit their answers to the task:

The row-level locks due to the task resubmission are represented in red, and the blocked queries from users submitting their answers to the task, waiting to update these locked rows, are represented in dark orange.

Each user waiting to submit his answers to the task holds one active database connection, resulting in the spikes seen previously. So why didn’t splitting the transaction solve the problem, and made it worse?

Well, that’s because splitting the transaction actually increased the chances of collisions in the “TaskStatuses” table! Initially collisions were only possible when resubmitting tasks. Then, with splitting, collisions became possible even in the first submission of a task, since users from the first batch could already be sending their answers before all task submission batches were entirely processed.

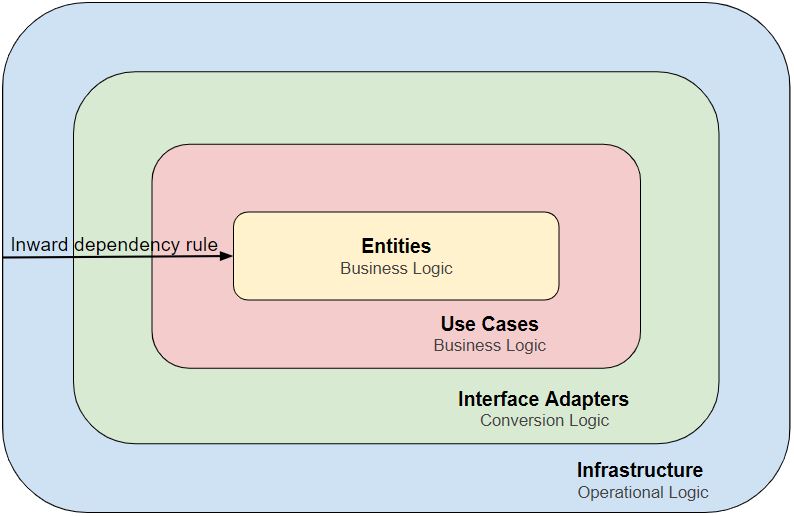

The (effective) Solution

To solve this problem and prevent blocking of the “TaskStatuses” table I implemented a mechanism in which a single agent is responsible for updating the “TaskStatuses” table, more specifically a queue worker, and everyone else is only allowed to perform insertions in this table.

Additionaly, I had to drop the TaskID-Status unique constraint and add an “ID” primary key column to the “TaskStatuses” table, whose purpose I explain below.

When submitting a new task, or resubmitting an existent task, one row with PENDING status and “1” count is inserted for each user that received this task. Then a queue message is sent to the updating agent to aggregate rows for this task.

When a user submits his answers one row with PENDING status and “-1” count is inserted and another row with DONE status and “1” count is also inserted. Then a queue message is sent to the updating agent to aggregate rows for this task.

When the updating agent receives a message it first fetches all rows IDs for the specified task:

SELECT ID

FROM TaskStatuses

WHERE TaskID={TaskID};

Then it executes an aggregation query based on the resulting IDs:

SELECT Status, SUM(Count)

FROM TaskStatuses

WHERE ID IN ({RowsIDs})

GROUP BY Status;

And finally it deletes all of these rows, and inserts the results from the aggregation query, all within a database transaction, thus effectively keeping the “TaskStatuses” updated and removing duplicate status entries for the same task.

Of course, since this process isn’t atomic, it’s possible, and quite easy actually, to spot duplicate status rows for a task which was not yet processed by the updating agent. However, the system can handle this transitional table state by simply sticking to the following aggregation query whenever reading this table:

SELECT Status, SUM(Count)

FROM TaskStatuses

WHERE TaskID={TaskID}

GROUP BY Status;

This solution proved quite successful, reducing experienced active database connection spikes “heights” to half of what they used to be, on average:

In this article I presented a strategy for dealing with aggregation tables locking problems. It was effective for my case, and can also be effective for you if you’re dealing with a similar problem. To apply it you will have to change how you’re writing to and reading from the aggregation table and also create an agent responsible for aggregating and cleaning up rows, which I saw fit and implemented as a queue worker.