As software developers, fixing bugs is part of our jobs. Over the course of the years we end up investigating and solving hundreds, thousands of them, and mostly inevitably we become increasingly skilled at it.

So why is that we become much better at solving bugs, and how can we leverage this knowledge to guide new developers for becoming better bug solvers (and also problem solvers) as well? One answer, based on my experience and observations, is that experienced software developers are really fast at determining the root cause of bugs.

If we look at an established problem solving process such as Toyota’s eight step process1 we can see that most uncertainty is contained in steps “1” through “4”, which are concerned with searching the root cause of the problem:

- Clarify the problem

- Breakdown the problem

- Target setting

- Root cause analysis

- Develop countermeasures

- See countermeasures through

- Monitor results and processes

- Standardize successful processes

It’s arguably really difficult to accurately estimate how long it will take to find out the root cause of a bug: there are those that take only a few minutes, others a couple of hours and some even days! Nonetheless, once the root cause is found and confirmed the next steps can be quite easily estimated, planned and carried out.

Hence, my proposition is that in order to become more effective bug solvers we inevitably need to become better bug investigators, i.e., better at searching and confirming the root cause of bugs. In the next sections I derive a simple framework for root cause analysis inspired by my own observations and by the analysis of competing hypotheses (ACH) methodology2, which is aimed at evaluating multiple competing hypotheses for observed data in an unbiased way.

The Framework

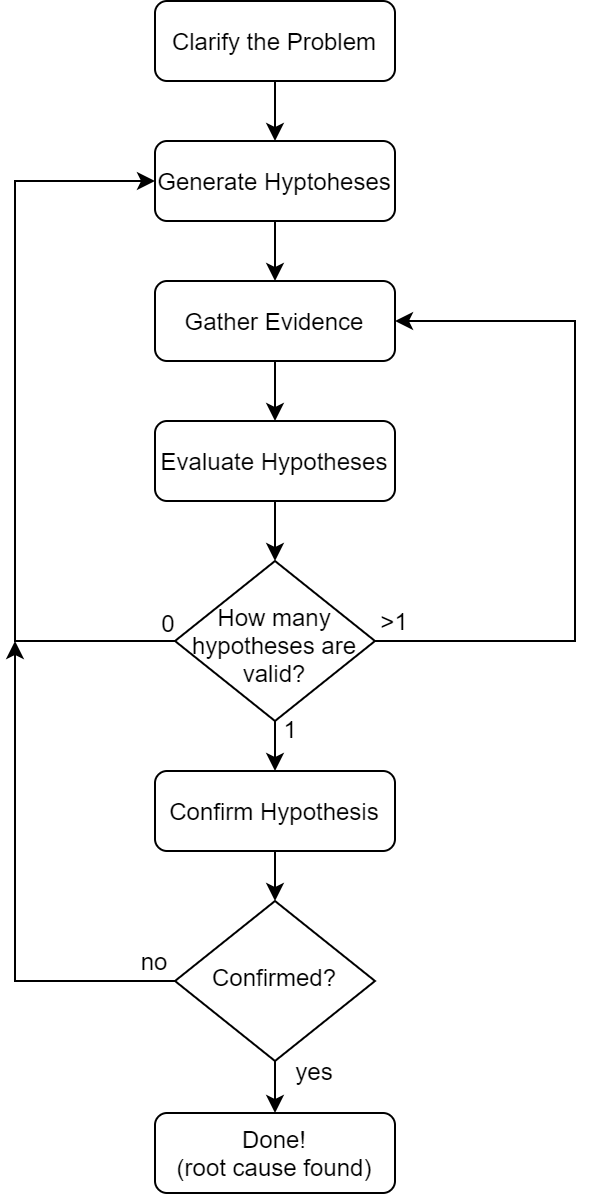

The proposed framework has five steps and is presented below. It’s centered at hypotheses generation and evaluation through gathered evidence, and the way these steps are performed, as we’ll see, varies greatly according to the experience level of the developer:

1. Clarify the Problem

The first step is to describe the problem, or bug in our case, clearly so to remove any ambiguity from its definition. All parties involved in sorting a bug out must agree on what the problem is, and what it isn’t. Asking a few questions about the conditions in which the bug surfaced already go a long way in this matter, helping bringing up relevant application use cases that have failed:

- What were you trying to achieve?

- What steps did you take?

- What should have happened?

- What happened instead?

Junior developers are more prone to take this step for granted and jump right into the next steps without making sure all parties involved share the same definition of the problem as he/she does. Senior developers, however, will only proceed after reaching out all parties involved to ensure everyone is on the same page in regard to what the problem is and how to reproduce it.

By not performing this simple step appropriately a developer is risking spending valuable hours solving the wrong problem, and over the past ten years I can say that I’ve seem this happen several times.

2. Generate Hypotheses

Once everyone agrees on what the problem is it’s time to brainstorm hypotheses on why it’s happened, i.e., what’s causing the bug. Based solely on a clear problem definition and technical knowledge of a product it’s already possible to come up with several candidate hypotheses.

Tougher bugs generally yield to less specific hypotheses at first, but as we iterate over the framework’s steps and our comprehension of the problem improves we’ll be able to refine them for narrowing down a probable root cause.

Let’s use an example to illustrate this step, suppose we are dealing with a bug in a GPS navigation application:

- Route calculation from address A to address B produces a non-optimal more costly route when using the “find cheapest route” feature

Out of the box a developer may propose the following hypotheses:

- The “find cheapest route” feature is not being activated, and the standard route calculation algorithm is being used instead

- Road pricing (tolls) information is outdated in the application, and the “find cheapest route” feature relies on it for calculating the right route

- The “find cheapest route” feature algorithm is faulty, and the bug definition describes a failing test case

- The more costly route is the only one available due to ongoing circumstances (“not a bug” hypothesis)

Each one of these hypotheses will go through an evidence gathering step and an evaluation step in order to invalidate the majority of them, and finding out the one that eventually holds true.

In this step Senior developers have a clear advantage usually due to having i) an extensive past record of bugs solved and their root causes ii) a deep knowledge of the product and business rules iii) a deep knowledge of the product’s technology stack. Under these circumstances, for what he/she’s seen and knows, a Senior developer is able to enumerate a much larger number of highly likely root cause hypotheses in a short time, when compared to Junior developers.

3. Gather Evidence

Evidence should be gathered with the goal of invalidating hypotheses, including: system logs, system metrics, analytics, screenshots, debugging sessions, etc. A skeptical mindset for gathering evidence helps us overcome common cognitive biases and being more effective in this process. Below I list a few cognitive biases that may affect our judgement on what evidence to seek for validiting a bug’s root cause hypothesis:

- Availability bias: the tendency to think that examples of things that come readily to mind are more representative than they actually are.

- Confirmation bias: the tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information that confirms or supports one’s prior personal beliefs or values.

- Information bias: the tendency to seek information even when it cannot affect action.

- Illusion of validity: the tendency to overestimate one’s ability to interpret and predict accurately the outcome when analyzing a set of data, in particular when the data analyzed show a very consistent pattern.

Besides being more susceptible to cognitive biases, it’s not uncommon for Junior developers to not use all available information sources for collecting evidence, eventually leaving out key evidence in a first iteration, only to come back to it again in future iterations, misspending valuable time. Senior developers, however, will in general know where to look for evidence, and what to look for, hardly leaving anything important out of the analysis.

4. Evaluate Hypotheses

Despite the more illustrative flowchart given above in which this step is presented as coming up only after one has completed generating hypothesis and gathering evidence, it’s actually performed somewhat simultaneously to steps “2” and “3”.

I see this step as an ongoing mental process that happens while hypotheses are being generated, as to evaluate their feasibility, and while evidence is being collected, as to evaluate the impact of new evidence on the set of candidate hypotheses being considered.

The cyclical procedure formed by steps “2”, “3” and “4” is similar to a feedback loop that continuosly refines the set of candidate hypothesis based on a growing context of “diagnostical” evidence against which these hypotheses are evaluated.

This cycle is performed until a single hypothesis remains valid, in which case we proceed to the confirmation step. Otherwise, if more than one hypotheses hold, one should still seek for evidence to invalidate them. In case none hypothesis hold, we’ll have to go back to step “2” for brainstorming new hypotheses.

Critical judgement and logical thinking play a central role in this step. Developers are required to analyze facts (evidence), extrapolate them and make effective decisions. Oftentimes we are faced with incomplete evidence having to evaluate in a timely constrained situation whether it’s strong enough to make a decision. Junior developers may not yet have a fully developed mental framework for making effective decisions in the context of an application/product they’ve just recently started working in, hence the importance of more experienced developers to assist them while they develop these skills.

5. Confirm Hypothesis

Finally, when there’s a single hypothesis left it goes through a confirmation step similar to the previous evaluation step, but entirely focused in proving that the bug root cause was indeed found. Two general strategies are provided below:

- The tracing strategy: Since the problem is clarified and a probable root cause established, in this strategy we employ tracing techniques and verbose logging to create a track record that will allow for confirmation upon reproducing the bug.

- The exploitation strategy: Complementary to the first, in this strategy we exploit the probable root cause for defining new test cases whose outcomes shall be consistent with said root cause, corroborating it.

It’s possible that while trying to confirm the hypothesis we end up invalidating it or discovering it’s not yet actionable, i.e., not specific enough for a developer to start working in a solution, and if that’s the case we’ll have to go back to step “2”.

Again, Junior developers often rush into coding a bug solution before properly confirming it’s root cause. More experienced developers know that it’s much cheaper in the long run to always confirm the root cause before starting to code a fix.

Conclusion

Wrapping up, the framework proposed in this article tries to capture a functional mental model for investigating a problem’s root cause. Key characteristics seem to differentiate senior developers from junior developers in regard to their speed in determining the root cause of bugs, namely:

- Extensive knowledge of the product and technology stack

- The ability to produce highly likely hypotheses

- Critical thinking mindset for seeking and evaluating evidence

- Meticulousness upon which each step is carried out

One can improve himself in these matters up to a point by simply becoming aware of their role and importance. Proper guidance can take a developer even further. However, only years of practice solving a generous amount of bugs will eventually lead to proficiency.

Sources

[1] Phillip Marksberry, PhD, PE. The Modern Theory of the Toyota Production System: A Systems Inquiry of the World’s Most Emulated and Profitable Management System. Productivity Press, 2012.

[2] Richards J. Heuer Jr. Psychology of Intelligence Analysis. Center for the Study of Intelligence, 1999.